| (1) Factionalized

Government |

In the 16th century, the

Sarim scholars became officials of the central

government and confronted the old scholars who were in

positions of power in the government. The two factions

participated in the administration of the government

under King Songjong with different political views but

did not often confront each other.

Immediately after

Prince Yonsan came to the throne, confusion ensued in

politics. The existing and new factions engaged in a

political struggle which has come to be known as

"Sahwa," the bloody purge of scholars. When Yonsan was

dethroned and Chungjong became King, the new Sarim

forces attempted to administer to the government a

Confucian idealism centered around the scholar Cho

Kwang-jo.

However, their policies of reform failed as

a result of opposition by the old faction. This drove

the government into a state of confusion. Later, the

political scene worsened, as conflicts within the

queen's family increased in severity.

Under the reign

of King Sonjo, the new Sarim forces led the nation's

activities and Sarim politics began. There were,

however, political differences among the Sarims and

factionalism arose. They carried out a particular form

of governing by restraining the growth of any one

particular faction and taking turns in possessing power.

This factionalism which began in early Choson became

more complicated as they entered the late Choson

Dynasty. Later factionalism grew even worse and had

negative ramifications on social and economic life.

These factional strifes were not corrected even after

the country experienced the great suffering of the

Waeran and Horan. Rather, factionalism grew in intensity

creating not only political confusion but divisions in

society as well. |

| |

| (2) The T'angp'yong Policy

and Restoration of Choson |

The many years of continuous

factionalism in politics brought about all sorts of

negative effects. There were deep concerns expressed

over such ramifications and during the reign of King

Sonjo, Yi I cautioned against the evils of

factionalism.

In the 18th century, Yongjo and Chongjo

promoted the T'angp'yongch'aek, a pacifying policy, in

order to check factionalism. They called the

representatives of each faction together, advised them

to get along, promoted people without making

distinctions on the basis of faction, erected the

T'angp'yong monument at the entrance of Songgyun'gwan

and even taught students. This policy, enforced with a

strong will, eliminated factionalism by refusing to take

sides with any one faction and thus achieved the

restoration of Choson.

Yongjo closed 300 Sowons,

enforced the Kyunyok law (balancing law) in order to do

away with evils within the military and restored the

Sinmun'go system in order to carry out politics

reflective of the wishes of the people. In addition,

many precious books were published and

distributed.

King Chongjo also promoted King Yongjo's

policy of strengthening royal authority. He especially

made efforts to achieve cultural restoration. He

established the Kyujang-gak (palace library) and

nurtured it as an institution of the crown for the study

of the arts, sciences and national policies. He also

ordered the compilation of a code of law called Taejon

t'ongp'yon, a pictorial text of the military arts, the

Kyujangchonun, a book on phonetics, Chungbo munhonpigo

(encyclopedia Koreana), the Ch'ungwan-ji, and the

T'akch'i-ji as national undertakings. The newly

organized Royal guards (Changyong yong) also

strengthened the military base of the royal authority.

|

| |

| (3) Reorganization of the

Tax System |

The law-abiding people of

Choson bore the three duties of paying farm taxes,

public imposts and corvees. Around the period of the

Waeran, tax collecting was a disorderly operation which

increased the difficulties of the people and thus

worsened with the Waeran and the Horan.

Only by

restructuring its system of taxation could the people

live in stability and the government increase its

revenue. Restructuring of the taxation system began

after the two wars and was all but completed by the 18th

century.

Land tax was imposed on farmlands. During

the two wars, much of the land was desolated and

government records of landholdings burnt. Land-surveys

and the rearranging of land registers increased the

acreage of arable land. However, the amount of land used

as palace farms and other royal land which was not taxed

increased, and the burden of tax-paying people also

increased. Thus, the government instituted and enforced

laws which lowered tax rates in order to lighten the

people's tax burden and which required fair imposition

of taxes.

There were also problems in operating the

system of paying imposts on certain farm goods

particular to various localities. From the beginning of

the nation, the system of paying imposts was enforced

but the system caused great suffering among the farmers.

Thus, the government ordered the payment of taxes not in

goods but in rice and the amount to be paid would be

determined by the law governing that region. This was

known as the Taedong Law.

The Taedong Law was

exemplarily enforced in Kyonggi-do through the proposal

of Yi Won-ik under the reign of Prince Kwang'hae and it

became a uniform law which was enforced in all the

provinces except for the P'yong'an and Hamgyong

provinces until the reign of King Sukjong.

Military

service was enforced through a system of universal

conscription and all peo ple were expected to serve.

However, from the time of King Chungjong, the military

service system was changed so that people would not have

to directly bear the burden of service instead, persons

with the financial resources could offer the government

cloth for military service. The government drafted

soldiers without financial income from these fabrics and

thus could maintain national defense. However,

establishing military organizations with such a system

of drafts was in reality unfeasible. There were many

abuses in imposting the amount of fabric for military

clothes which would have to be paid out. For example,

there were occasions on which people were forced to

provide military uniform clothing for soldiers who had

run away or were missing.

From earlier times, there

were efforts to do away with such aspects of military

service. King Yongjo enforced the Kyunyok Law. This law

decreased the number of Pil (a unit of measure for

cloth) that would have to be paid from two pils to one,

and the state received taxes from fishing, saltmaking,

and ships which originally had been collected by the

local office or the palace in order to fulfill its

financial needs. With changes in the tax system, the

burdens of the people decreased, but the abuses in

collecting taxes were not completely resolved.

|

| |

| (4) Increase in Farm

Production |

|

|

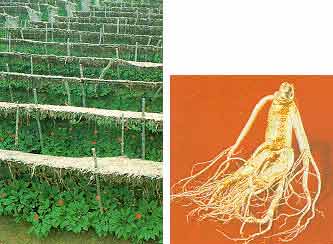

Ginseng : For over 2,000 years. Korea has

been recognized as the main producer of Ginseng.

The root played an important part in Korea's

political and economic relations with neightboring

countries. | |

| |

An effort to reconstruct the

farmland left desolated by the Waeran and the Horan wars

was undertaken by the government to stabilize the

people's livelihood.

Land surveys were carried out by

compiling land registers, land reclamation was

encouraged and the development of irrigation facilities

were enforced. Handbooks for farmers were published and

distributed in rural communities. The construction of

dams and reservoirs increased the number to 6,000

throughout the country by the end of the 18th century.

As a result of the expansion in irrigation facilities,

rice paddy fields increased. The rice transplanting

method which had been used by some farmers in the early

stages of Choson was popularized and reduced labor power

and increased production. The method of cultivating

barley in rice paddies after harvest was popularized. In

the area of dryfield farming, planting crops in furrows

was a common way to obtain a larger harvest.

By

reducing labor power through new methods of farming, the

per capita of arable farmland increased greatly and land

owning farmers who cultivated large acreages of land

also began to increase. Some of the owners who had large

pieces of land employed farm laborers to help them

cultivate the land. In the 18th century, commercial

products such as ginseng, tobacco, cotton, fruit, and

herbs were also cultivated in order to increase the

income of farm families.

To help in agricultural

development, books on agriculture were published. The

Kamjobo, Nongga chipsong (agricultural house

collection), Sallim kyongje (forest economy), and Imwon

kyongje-chi (forestry economy) are representative of

farmer's handbooks which appeared during this

time.

As the households in farming villages

prospered, mutual aid organizations such as Kye and Ture

formed in rural communities. |

| |

| (5) Commercial Developments

and the Circulation Organization |

During the early years of

Choson, except for city shops in Seoul which supplied

ordered goods and enjoyed prosperity under special

protection by the government, merchants remained

inactive. However, in later years, a system of barter

emerged and commercial activities underwent change.

After the enactment of the Taedong Law, the government

procured necessary goods and had them delivered. The

artisans who were responsible for providing these goods

were able to thus amass wealth through this system. With

the appearance of commercial crops and production goods

of "free" handcraftsmen in society, the private

merchants who handled such goods made their advent. The

city shopkeepers tried to interfere with the activities

of these merchants by banning them, to no

avail.

Under the reign of King Chongjo, a policy of

free commercial activities eliminated restrictions

against private dealers and commercial activitities of

free merchants increased.

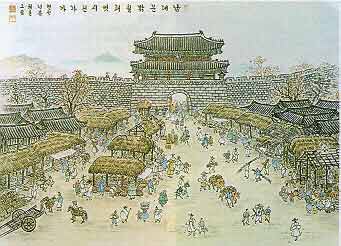

In the countryside, markets

became active, regular markets appeared in each local

region and in the large cities, permanent markets

opened. In the markets of local regions, merchants and

peddlers made their transactions. In the middle of the

18th century, about 1,000 markets opened. Following the

development of these markets, roads were improved and

currency was circulated in large amounts to facilitate

trade. With the emergence of Kogans, a type of

middleman, and facilities such as Yogak and Kaekchu,

commerce and trade flourished. |

| |

|

A

picture of an old market place outside Namdaemun

Gate. | |

| |

Parallelling the development

of domestic commerce, foreign trade also increased. From

the mid-17th century, as trade activities with Qing

increased, official and private trade activities were

carried on in Chunggangchin and Ceman in Fenghuangcheng

Manchuria. Leather, paper, cotton, and ginseng were

exported and silk, drugs, hats, and stationery were

imported. Trade with Japan was conducted through the

Waegwan (Japanese house) with Tongnae as its center,

exporting ginseng, rice, and cotton, and importing

silver, copper, sulphur, and pepper.

Free merchants

dealing in domestic goods accumulated huge fortunes. The

"Kyonggang" merchants of Seoul, "Songsang" in Kaesong,

"Yusang" in P'yong'yang, "Mansang" of Uiju, and the

"Naesang" of Tongnae were particularly well known for

their wealth. |

| |

| (6) Changes in Handicrafts

and Mining Activities |

In the early stages of

Choson, handicraft activities were under strong state

control because of a system of exclusively

government-commissioned handicraftsmen. However, the

road to private enterprises in production was gradually

opened. During the latter years of Choson, most

handicraftsmen paid artisan taxes to the state and

carried out their production activities as free

merchants. They manufactured paper, ceramics, brassware,

lacquerware, printing types, weapons, farm implements,

and other necessities of everyday life. After the

enactment of the Taedong Law, Kong'in (suppliers of

goods on demand for the government), appeared and other

handicraftmen produced large quantities of handicrafts

through the support of wealthy capitalist merchants, who

provided goods for Kong'ins.

With growing demand for

silver, trade with China increased and silver mining was

actively pursued. By the end of the 17th century, 70

silver mines were in operation. At this time,

developments in gold mining were also made. Copper

mining was developed actively for copperwares, weapons

and copper coins.

However, enterprising miners and

merchants, because of the heavy burdens of taxes,

mobilized their capital in order to develop and gather

underground resources. |

| |

| (7) Changes in the Social

Status System |

The Choson society was a

Yangban-centered society. Severe discrimination existed

between the Yangbans and the ordinary people. Among the

Yangbans, there were those who, as they went from

generation to generation, put on airs of pretension, and

there were Yangbans in the countryside who outwardly

maintained their social status in spite of economic

bankruptcy. Among some farmers, there were those who,

either through distinguished service in war or providing

assistance to the national economy during times of

difficulty, were granted Yangban status in recognition

of their patriotism. As a result of increased royal or

landlord owned farmlands, farmers who lost their land

were forced to become either hired farm laborers or day

workers.

Among slaves, who were recipients of the

most contemptible treatment in society, there were

increasing numbers who were given the status of common

people in gratitude for their military exploits. Because

an increase in draftable soldiers and tax payers meant

increases in national revenue, the state tolerated the

rise of slaves to the status of common people. Thus, by

1801, except for a minority, a total of 66,000 public

slaves were liberated to become law-abiding citizens of

the state.

Technical workers, illegitimate sons of

Yangbans, and local officials in government were

referred to as the middle class and were recipients of

discrimination. Following the changes in the social and

economic situation in the latter period of Choson, these

persons made efforts to elevate their social

status.

The Yangban-centered status system was

affected, and movement between each social stratum was

evident but was inadequate to overturn the historical

trends. Thus, the structure of Yangban domination

continued as before. | |