| (1) Restructuring Domestic

Politics and Expulsion of Foreign Aggressors

|

Around 1860, the Choson

Dynasty faced difficult external and internal problems.

Internally, the foundation of national law and order

weakened as a result of "Sedo" politics. This period,

which spanned 60 years, saw the manifestation of both

severe poverty among the Korean population and ceaseless

rebellions in various parts of the country. Externally,

Catholicism spread far and wide throughout the country

and foreign ships appeared on Korea's coasts to request

commercial activities with the Choson Dynasty.

Such

domestic and foreign conditions spawned feelings of

crisis throughout the whole nation. Thus, the Korean

people demanded that the government stabilize the

livelihood of the people, check the inroads into Choson

by western powers, and bring national peace. At that

time, the Hungson Taewon-kun, the Regent, who

represented King Kojong who was a child at the time,

courageously enforced reforms in order to overcome

internal and external crisises confronting the

nation.

In order to get rid of the evils of "Sedo"

politics, he promoted persons without making references

to political party or family affiliations, and in order

to reduce the burdens of the people and solidify the

basis of the nation's economy, he reformed the tax

system. In order to establish order through law and

strengthen royal authority, he also reorganized

government organizations, destroyed Sowons and rebuilt

Kyongbokkung Palace.

Under the rule of Hungson

Taewon-kun, the Choson government and people bravely

fought against aggressions by the Western powers. After

a month of fighting, the defenders of Choson drove out

the French army, who had invaded Kanghwa Island to

protest the persecution of Catholics in 1866. During

this period the U.S. military presence was also driven

out in 1871. The U.S. had invaded the Choson regime in

retaliation of the burning of a merchant ship on the

Taedong River in P'yong'yang. |

| |

|

Kanghwa Fortress, assaulted by the French

in 1866, has recently been restored and epuipped

with a modern

cannon. | |

| |

After successfully checking

aggressions by the French and American armies, the

Choson government further strengthened its closed door

policy. At important locations in Seoul and throughout

the country, monuments were erected to inspire people to

fight against aggressions by Western powers.

Furthermore, the Japanese were driven out for being

Orangk'aes (barbarians) since they maintained relations

with the West.

The anti-foreign powers policy led by

Hungson Taewon-kun received enthusiastic support from

the people, because they felt threatened by potential

aggression. However, this closed door policy was not an

adequate measure against the great current of world

affairs, and thus, it further delayed the modernization

movement of Korea. |

| |

| (2) Opening of Ports and

the Enlightenment Policy |

| Hungson Taewon-kun left the

government after 10 years of serving as Regent. He later

became friendly to the idea of exchanges of civilization

with foreign powers and as a result Choson's foreign

policy began to open ports and engage in commercial

activities. But before the government was fully prepared

to open its ports, Japan invaded Kanghwa Island and

demanded further openings. Consequently, Choson was

obliged to sign the first modern treaty of amity with

Japan in 1876. The government also concluded treaties of

amity and commerce with the United States, England,

Germany, Russia, France and other nations. |

| |

|

A

Chosun KingDom militia undergoing

an inspection

in SEoul | |

| |

Although Choson entered the

international arena by signing treaties with various

nations, the treaties signed during these times were

unfair to Choson. For through these treaties, Choson was

forced to permit the rights of low tariff rates,

extraterritoriality and residence of foreign nationals

in Choson's open ports. This in effect, prepared a

springboard for possible political and economic

aggressions against Choson by these nations.

Choson,

which signed these treaties for diplomatic and

commercial trade, made many efforts to accept the

modernity of the West.

The government dispatched Pak

Chong-yang and other officials to Japan to observe

modern institutions and industrial organizations. In

addition, it dispatched Kim Yun-sik and other

bureaucrats to China to study methods of manufacturing

modern weapons and training the army.

In order to

modernize, the Choson government revamped its political

and military organizations. The central government

established 12 ministries under the T'ongni kimu amun to

take charge of such duties as diplomacy, military and

industry. Among new developments in the army, special

military forces were organized and provided with modern

military training. Furthermore, Choson accepted the

proposals made by officials dispatched to foreign

countries to set up modern machinery plants.

|

| |

| (3) The Military Rebellion

of 1882 |

When the government

continued to promote modernization of the West,

Confucian scholars developed strong opposition

movements. They insisted on fighting the foreign powers

when France and the U.S. ships invaded Kanghwa Island

and the government signed the Treaty of Amity and

Commerce with Japan. These Confucian scholars possessed

a strong sense of subjective power, thus they advocated

the guarding of Choson's traditional culture and systems

which were believed to be superior to the West. Amid the

conflicts between the forces of reform and conservatism,

a military rebellion known as the Imo Military Rebellion

broke out in 1882. At that time, the old military was

discriminated against in comparison to the new military

(Pyolgi-gun) and were unable to receive their salaries.

When they finally received their wages in rice mixed

with sand and chaff, they rose up in rebellion. They

drove out the Queen's family (Mins), propelled reform

measures, and grasped political power by putting Hungson

Taewon-kun in power again.

However, China mobilized

troops to kidnap Hungson Taewon-kun and by oppressing

the old military, the Mins once again held political

power. In this process, interventions by China and Japan

were so severe that Choson was placed in an even more

difficult position. |

| |

| (4) The Coup d'Etat of the

Reform Party |

The Mins, who again took

over the government by borrowing China's strength,

utilized reform-oriented officials to enforce

progressive enlightenment policies. However, due to

increased domestic intervention and economic

exploitation by China, the policies of reform promoted

by the government could not proceed

smoothly.

Hereupon, Kim Ok-kyun and the radical

reform forces instigated changes in Choson's political

and social systems by utilizing unorthodox means. They

killed and wounded high officials of the Min family, who

were participating in a ceremony commemorating the

completion of a post office building, by utilizing some

members of the military and the Japanese army.

Additionally, they persuaded King Kojong to join their

side and thus managed to grasp political

power.

Members of the radical reform forces who were

newly appointed as government officials attempted huge

reforms in all fields in order to build Choson into a

wealthy modern nation with a powerful military. They put

forth a platform of reform and declared that they would

do away with discrimination along family lines,

establish equality for all people, amend tax laws, unify

the financial agencies, establish a police system and

modernize the administrative system.

But before these

reforms were enforced, the radical reform party was

expelled from political circles and their reform

measures dropped. The forces of conservativism borrowed

the strength of Chinese power to hold on to government

control and the forces of radical reform became

political refugees who fled to Japan and America.

The

reasons behind the failure of the radical forces were

that they failed to make thorough preparations, did not

obtain the support of the people and attempted to retain

political power through the help of Japan which always

placed them in danger of betrayal. The new Choson

government which was based on the coup d' tat pursued

policies of gradual and healthy reforms, but due to

Chinese intervention and economic aggressions by Japan,

the livelihood of the people became even more

endangered. |

| |

| (5) Tonghak Movement

|

To check the powers of China

and Japan, the government of Choson utilized Russia.

Russia, which had just finished constructing a military

post in Vladivostok and was promoting a policy of

southward expansion, hoped to use this opportunity to

maintain military bases on Ulung Island and

Masanp'o.

But England, which hoped to counter the

southward expansion policy of Russia, dispatched a fleet

to the Far East to occupy Choson's Komun Island where

she built a military port. The government of Choson

strongly protested this unjustifiable act by England and

after many months of negotiations, forced England to

withdraw from the Island in 1887.

While Choson was

confronting the aggressions of both internal and

external forces, a new religious movement grew among the

peasants. The followers of Tonghak, who had organized a

large force, held demonstrations everywhere, in order to

clear up the accusations against the founder of the

religion, Ch'oe Che-u, who had been unjustly arrested

and put to death. In addition, they demanded that the

government allow freedom of religion, purge corrupt

government officials and drive out the Japanese and

Western forces.

The actions of the followers of

Tonghak proceeded into an all-out peasants' war-the Kobu

Rebellion (1894). The Kobu Rebellion was a limited

uprising which broke out in protest against the tyranny

and abuses of the magistrate, Cho Pyong-kap, but as a

result of the merciless oppression by the government,

all the peasants in both the north and south Cholla

provinces rose up in an uprising which spread throughout

the whole nation within a short time.

The peasant

army under the command of Chon Pong-chun annihilated the

government troops and occupied all of the Cholla

Province. The government, realizing that it was unable

to suppress the peasants' army alone, requested that

China dispatch its troops. Thus, the government promised

the peasants that it would listen to their demands and

ordered them to dissolve their troops.

At the time,

the peasants' army had demanded: the punishment of

corrupt officials, tyrannical men of wealth and

Yangbans; abolition of the social status structure;

waiver of public and private debts; equal redistribution

of land; and expulsion of Japanese forces. When the

government promised to accept the above demands, Chon

Pong-chun dispersed the peasants' army. In addition,

they organized offices in 53 counties under their

occupation so that the peasants themselves would take

part in carrying out such reforms.

While the peasant

movement was beginning to take the first steps toward a

resolution of the problems with the peace agreement

between Chon Pong-chun and the government, China and

Japan dispatched troops into Choson and the

Sino-Japanese War erupted. Japan, in particular, had

ambitions of occupying Choson and when she was convinced

that victory over China was certain, Japan mobilized its

military forces. Japan then drove China out of Choson

and marched south with the government army as its

puppets to suppress the peasant army.

The 200,000

peasant troops under Chon Pong-chun's command engaged in

repeated battles with Japan. But they were no match for

the modern Japanese army. Thus, the peasants movement,

which had had as its objectives revolutionary reform

within government and society, in addition to the

expulsion of foreign forces, ended in failure.

|

| |

| (6) Reforms in the

Political and Social Systems |

Japan which had sent troops

under the pretext of suppressing the peasant movement,

demanded that the Choson government make internal

reforms. This demand to change the political and

economic systems of Choson into Japanese-like systems

was made in order to accommodate the Japanese invasion

of Choson.

The government, which was receiving

pressure from the population for huge reforms, could not

but form some kind of proposal for reforms in the social

and political systems. Thus, the government set up a

special agency called the Kun'guk Kimuch'o, which

carried out 208 types of reforms in the government, the

economy and society (Kabo Reform).

Reforms in the

political system included separating the duties of the

palace from governmental duties, abolishing the civil

service examination, separating the judiciary from other

functions, and reorganizing local administration

systems. Economic reforms included unification of the

financial offices, improvements in the system, and

uniformity of standards of weights and measures. Among

social reforms, the social status system was abolished,

widows were permitted to remarry, and torture and

punishment for people who had affiliations with

criminals were eliminated.

There were many positive

aspects in these measures by the government to change to

the premodern political and social orders. However,

because the Japanese were behind these changes, there

was much resistance. To suppress the objections, Japan

mobilized its army and "Nang'ins" (political thugs) to

murder the Empress Myongsong in 1895.

Under

aggravated Japanese pressure, the government spurred on

with even more reforms. These included the use of the

solar calendar, enforcement of vaccinations,

establishment of primary schools, establishment of a

postal service, use of the numerical year system, and

enforcement of cutting the traditional long hair.

But

since these reforms did not reflect the will of the

people, opposition was inevitable. |

| |

|

Stamps used during the Taehan Cheguk period

(1884~1907). | |

| |

| The Choson people were well

aware that Japan, as a means to occupy, had demanded

internal changes and had murdered its queen. The rise of

the anti-Japanese righteous army nationwide reflected

such an atmosphere. |

| |

| (7) The National

Self-Reliance Movement of the Independence Council

|

As Japanese intervention in

internal affairs increased in severity, King Kojong fled

to the Russian Legation and set up a new cabinet in

1896. He also engaged the Russian forces and began to

carry out a policy to restrain the Japanese forces. The

government's pro-Russian policy was effective in

checking the Japanese forces, but it also resulted in

greatly damaging the self-reliance of the nation.

At

this juncture, some officials and people of Choson made

moves to promote national self-reliance, independence,

strengthening of the nation and free rights for the

people. This was known as the movement of the

Independence Council.

Among the important figures in

the Independence Council were So Chae-p'il, Yun Ch'i-ho

and Yi Sang-chae. They erected the Independence Arch and

Independence Hall and published a newspaper to promote a

consciousness of national self-reliance among the

people. In addition, they held discussion rallies in

Seoul and other important regional cities, denouncing

the Government's policy of depending on foreign forces

and stood in the frontlines of enlightening the people

on modern political thought.

The activities of the

Independence Council were a great impetus to the

government and the people. The Independence Council

advocated a political system composed of a

constitutional monarchy and a parliament, and in

diplomacy it called for diplomatic relations based on

the principle of self-reliant neutrality. Socially, it

advocated the promotion of people's rights, namely, the

rights to existence, freedom and equality. |

| |

|

|

Tongnim-mun (Independence Gate) and

Tongnip-kwan (Independence Hall). With donations

from the private sector, the Tongnip hyop hoe

(Association for Independence) erected Tongnim-mun

in 1898 as a way to instill a spirit of

independence and patriotism among the

people. | |

| |

At one time, the government

accepted the above proposals of the Independence Council

and adopted postures to execute them. However, the

government, feeling that the demands of the Independence

Council and the citizens were encroaching on the

privileges of the Emperor and the ruling classes,

suppressed and dissolved the Independence

Council.

Although the movement of the Independence

Council ended in failure, it contributed greatly to

planting a consciousness for modernization and national

self-reliance in the hearts of the people. This

consciousness also became the ideological basis for the

anti-Japanese movement later on. |

| |

|

|

|

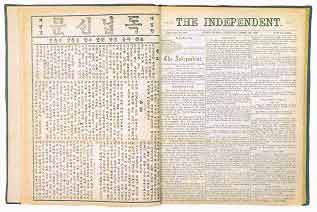

The

first edition of Tongnip Sinmun(The independent) :

First published on April 7.1896 by

So Chae-pil

as the official publication of the Tongnip hyop

hoe (Association for independence), it was Korea's

first non-governmental newspaper. |

Emperor

Kojong | |

| |

| (8) Establishment of the

Taehan Cheguk and Policy of Self

Empowerment |

King Kojong who had taken

refuge in the Russian Legation for the past year,

returned to Kyong'unkung Palace (now Toksukung Palace)

at the height of the activities of the Independence

Council. The people renamed his country Taehan Cheguk

(the Great Han Empire) and proclaimed to the world that

Taehan Cheguk was a self-reliant nation in 1897.

Furthermore, he enforced various reforms in politics and

set about to establish a powerful and wealthy

country.

The Taehan Cheguk government expanded a

program of new education and set up a Central Council to

reflect the will of the people, but when the

Independence Council and the people expanded their

political movement, the government supressed them and

took measures to strengthen its own imperial

power.

The government promulgated nine articles of

the laws of the Taehan Cheguk which granted full

authority of command of the legislature, the executive,

and diplomacy to the Emperor and infinite imperial

authority in 1899. To establish the national economy and

improve the people's lives, it enforced policies to

carry out land surveys and encourage industries. The

establishment of various manufacturing factories,

sending students abroad, strengthening industrial

education, improving transportation as well as

communication facilities and the establishment of

hospitals were the chief policies of the Taehan Cheguk.

With the proclamation of Taehan Cheguk, the various

reform policies of the government heightened national

autonomy and aided in the wide acceptance of modern

civilization. However, severe party strife within the

government impeded these reform policies, and since they

were not consistently enforced, they were not able to

completely check interventions by foreign forces.

For

these reasons, peasants of the Yonghak-dang (offsprings

of the former peasant movement) in the Ch'ungch'ong,

Cholla, and Kyongsang provinces continued to demand

social and economic reforms. In addition, the

Hwalbin-dang forces, which were composed of merchants

and workers, sprang up in various places and demanded

social reform and the expulsion of foreign powers.

|

| | |