| (1) Founding of Choson and

Early Growth |

In the social confusion and

national crisis which ensued in the final days of Koryo,

the gentry and military explored means for establishing

a new state. With the withdrawal of the army from Wihwa

Island on the Yalu, military forces were strenghtened

and its new leaders drove out the old aristocratic

powers of Koryo and enforced a land reform program in

order to step up their economic basis. Then Chong

To-chon, Cho Chun and other powerful civilians placed Yi

Song-gye on the throne to establish a new state in

1392.

The name of the new state was Choson. This name

reflected a historical consciousness that it was

succeeding the traditions of Kojoson.

The capital was

fixed in Hanyang (now known as Seoul), located at the

center of the Korean peninsula, and the new reign strove

to win over popular support.

Choson's basic policies

were Confucianist politics, agricultural economy, and

pro-Ming diplomacy. In other words, it upheld

Confucianism in governing the nation, promoted

agricultural production in order to increase national

revenue and stabilize the lives of the people, and urged

for peace and stability by promoting friendly relations

with the Ming Dynasty, a newly rising power in the Asian

continent.

Since the national structure was

stabilized under the reigns of Kings T'aejong, Sejong

and Sejo, Choson became a Confucian state and adopted a

system of centralized power. With the completion of

Kyongguk taejon during the reign of King Songjong, laws

for government were provided.

Moreover, the national

territory as it is known today was established during

this period. During the reign of King Sejong, the

Nuzhens on the Yalu basin and the Tumens were driven

out. Four counties and six ports were set up along these

basins. With this, the Choson Kingdom, bordered by the

Yalu and Tumen Rivers, fixed its territories.

Additionally, policies of resettling people from the

southern to the northern territories was enforced for

the balanced development of the land. |

| |

| (2) Firm Establishment of a

Ruling Structure with Centralized Power

|

During the initial stage,

meriting vassals had grasped substantial political

power. However their powers were gradually taken away or

absorbed by the royal authority and governing powers

were centralized to the royal authority.

T'aejong

readjusted the bureaucratic structures and abolished the

practice of building private armies, and governing

powers were centralized to the King. He enforced

economic reforms in the temples and by increasing the

number of those considered citizens, he expanded the

basis of national revenues. These reforms stimulated the

growth of national culture and expansion of national

territory. King Sejong greatly contributed to the

development of the Choson dynasty through the

centralized government structure.

The supreme

administrative organization was known as the Uijongbu.

It was comprised of the Yonguijong, Chwauijong and

Uuijong. These consultative councils decided on national

policies which would have to be approved by the

King.

Under the Uijongbu, six ministries--Personnel,

Finance, Rites, Military, Justice, and

Construction--were set up as executive ministries for

national administration. In addition, Inspection and

Censor Boards as well as the Hongmun-gwan were set up to

ensure that the government ran smoothly.

As local

administrative organizations, the country was divided

into eight provinces where governors were dispatched to

take charge of their administrations. Within a province,

smaller administrative districts known as Mok, Kun and

Hyon were organized and local rulers known as Pusas,

Moksas and Hyollyongs were dispatched.

The military

service was enforced by a universal conscription system.

All male farmers above the age of 16 were obliged to

fulfill their duty of military service by bearing arms

or paying for some military expenses.

Five general

headquarters commanded the five central guards.

In

the border areas and at important military locations,

army and navy barracks were established and army and

navy commanders were dispatched from Central

Headquarters to command the fighting forces.

|

| |

| (3) Yangbans and

Bureaucrats |

The governing class of Choson

were known as Yangbans. Originally, Yangbans were

civilians and military bureaucrats who gradually became

the ruling governing class. They enjoyed many

privileges.

They advanced to become bureaucrats

through the civil service examinations, but some of the

sons of the upper level bureaucrats, who possessed many

special privileges, became bureaucrats without having to

pass the civil service examinations. |

| |

|

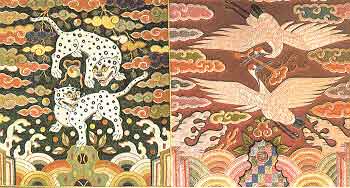

The

pair of tigers or cranes on these insignias were

attached to the front and back of the garments

worn by Chosun Kingdom high officials.

Military officials (left).

Civil officials

(right). | |

| |

Among the Yangbans, the

civilians were given preferential treatment over

military men. Also within the Yangban class, children of

illegitimate birth were discriminated against and

restricted from advancing in society.

Yangbans did

not engage in productive labor. They read the Confucian

classics or history books and lived their lives

according to Confucian rites. |

| |

| (4) The Policy of an

Agriculturally-Based Livelihood and the

Farmers |

Continuing the tradition of

developing agriculture as the foundation for the nation,

the Choson dynasty enforced agriculturally-based

livelihoods for farmers as the basic policy of the

state.

The government made efforts to reclaim land,

expand irrigation facilities, reform farming techniques

and raise silkworms for weaving. For these reasons,

during the early years of Choson, the amount of arable

land increased greatly, farm productivity rose to

augment state income, and the lives of the farmers

stabilized to some extent.

The system of land

distribution was based on the Kwajon system. According

to this system, bureaucrats were given pieces of land

commensurate with their ranks, as well as to government

officials. However, under the reign of Sejo, this land

distribution system was repealed and a new system known

as the Chikchon law was instituted. This system only

provided land to active bureacurats. In addition, there

were the private lands of government officials, the

crown lands, government lands, and self-owned lands of

the farmers.

All these lands were cultivated by the

farmers. Among farmers, there were those who owned the

land they tilled, but the majority of them were tenant

farmers. The tenant farmers were, by law, compelled to

offer half of their harvest to the landlords as a form

of payment for living on and tilling the land.

The

farmers were also compelled to provide taxes, imposts,

and corvee to the state. The taxes were paid in kind,

and were placed on the land. Public imposts were placed

on agricultural products particular to the locality. The

burdens of these imposts were so heavy they caused great

suffering for the farmers. |

| |

|

A

genre painting by the 18th century Sin yun-bok

depicing a village during

harvest. | |

| |

| Corvees were systems which

mobilized farmers for compulsory labor in the areas of

civil engineering and national defense. These were

obligatory for adults between the ages of 16 and 60

years. A large portion of the financial revenue of the

state was taxes, imposts and corvees which were paid by

farmers. |

| |

| (5) Commerce, Handicrafts

and Communications |

In the early period of

Choson, agricultural developments resulted from the

policy of self-sustaining, family-based agriculture. In

contrast, commerce and handicraft industries were late

in developing. In the heart of Seoul, many markets

existed including the government run Yuguijon. The

merchants of these shops obtained goods ordered from

government suppliers and even possessed monopoly rights

to sell certain items.

Shops also existed in regional

cities, but commerce was not heavy. In addition, there

were markets which opened once every five days, and

hawkers and packpeddlers known as "Pobusang" were the

main merchants. |

| |

|

Chosun period coins.

Sangpyong-t'ongbo.

17th~18th

century. | |

| |

In the handicraft industry,

government-run handicraft commerce activities were the

centers. Artisans were affiliated to central or local

governments and were responsible for goods needed by the

state. They produced weapons, printing types, stationery

and ceramics. Furthermore, farm households which made

handicrafts on the side were merely

self-sufficient.

Harvests in regional areas were

shipped through transportation organizations known as

the Choun mainly to Seoul. The taxes collected in kind

(grain) from the regional areas were brought to rivers

and sea ports and were transported to Seoul.

As for

transportation and communication facilities, there were

Yoks (stations) and Wons (hotels).

On the important

transportation routes, Yoks were placed at 30 li (about

10 miles) intervals and on inconvenient routes Wons were

built. Boarding and lodging facilities were provided at

Yoks, as well as the means for transmitting official

letters, transporting tributes, and other needs of the

travelling official were also provided. Travelling

officials were also privy to station horses according to

the number of horses carved on their "Map'ae" (horse

plates).

Boarding and lodging accommodations were

offered to official travelers in Wons. |

| |

|

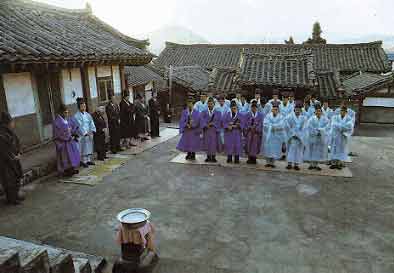

Ancestral rites are still widely practiced

in cities and the

countryside. | |

| |

| (6) Confucian-centered

Policy and Education |

The Choson dynasty utilized

a Confucian-based politics based on metaphysics. The

political ideal of the era was the realization of a

King-centered state. Thus, Yangbans had to research and

receive education on Confucian culture, and only the

civilian bureaucrats who rose to position by passing the

exams on Confucianism could hope to become high ranking

bureaucrats.

The ruling class, as it propagated

Confucian-centered state policies, suppressed and

changed traditional folk beliefs and Buddhism. But

Buddhism was able to preserve its life line as the

religion of commoners. In order to propagate a Confucian

consciousness among the people, the observance of the

Zhuzi garye of crowning top-knots, marriages, funerals

and offering sacrifices was mandated. Therefore, these

Confucian ceremonies were popularized during the Choson

Dynasty. |

| |

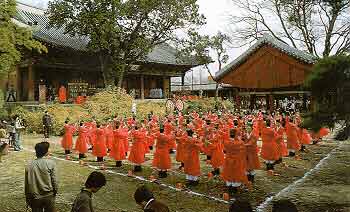

|

Confucian ritual, held each spring and

autumn at the confucian shrine in the confucian

college of Songgyun'gwan,

Seoul. | |

| |

The family system was

extremely important in Confucianism with the head of the

family as the center exercising absolute powers. He

presided over the ceremony of offering sacrifices to the

ancestors of the family. The Yangbans kept family

shrines and offered sacrifices on memorial days.

In

the Choson dynasty, the Confucian virtues of loyalty and

filial piety were highly valued. Loyalists, filial sons

and exemplary women received commendations from the

state and were highly respected. Confucianism became the

center of education. Four colleges in Seoul and regional

schools taught intermediate Confucianism. The highest

learning institute, Songgyun'gwan College in Seoul

taught advanced Confucianism.

Technical education in

the fields of medicine, astronomy, law, mathematics and

foreign languages was conducted by the government.

|

| |

| (7) The Growth of

Confucian Scholars and Their Advancement to

Seoul |

| Around the time Choson had

completed the building of its institutions, during the

reign of King Songjong, a new political force appeared.

They were referred to as Confucian students (Sarimp'a).

They were influenced by the scholarly works of Chong

Mong-chu and Kil Chae, who were loyal to the royal house

of Koryo. Kil Chae trained many students in his hometown

and later, Kim Chong-chik and his students became a

force in Yongnam (Kyongsang province). |

| |

|

Tosan

sowon, North Kyongsang province.

Built in

1514. | |

| |

The Confucian students

studied Songri philosophy which researched the study of

human nature and discounted other learnings and thoughts

as heresy. They also valued fidelity and duty and placed

importance on the classics.

During the reign of King

Songjong, Kim Chong-chik was promoted to a high position

and the Confucian students known as Sarim-p'a made their

entrance into the central political circles and

developed the Sarim faction. This force stood in

confrontation with the conservative party (Hunkup'a) who

held the major power in the King's court at the time. As

a result of the conflict between these two forces,

social turmoil erupted on several occasions. During the

reign of King Chungjong, the Sarim party headed by Cho

Kwang-jo propelled rapid reform measures. However, the

Sarim party's reform movement which hoped to realize the

political ideals of Sarim failed as a result of

opposition by the conservatives.

Members of the Sarim

party who were forced to return to their hometowns as a

result of this defeat set up Sowons in various locations

and popularized the idea of the Hyang'yak Contract which

advocated autonomy of country villages. Sowons were

places where Confucian followers cherished the memory of

the sages by offering sacrifices. The Sarims also

conducted research, studied and educated their children

in the Sowons.

With the development of Sowons and the

propagation of the Hyang'yak Contracts, Sarim forces

gained strength and Confucian morals were widely spread

throughout country villages. In addition, through the

research conducted by the Sarim forces in metaphysics,

this field flourished in 16th century Choson.

| |